Georgia, Inland Waterways, National Category

Startup Uses Drone for Cleaning Water, Collecting Data

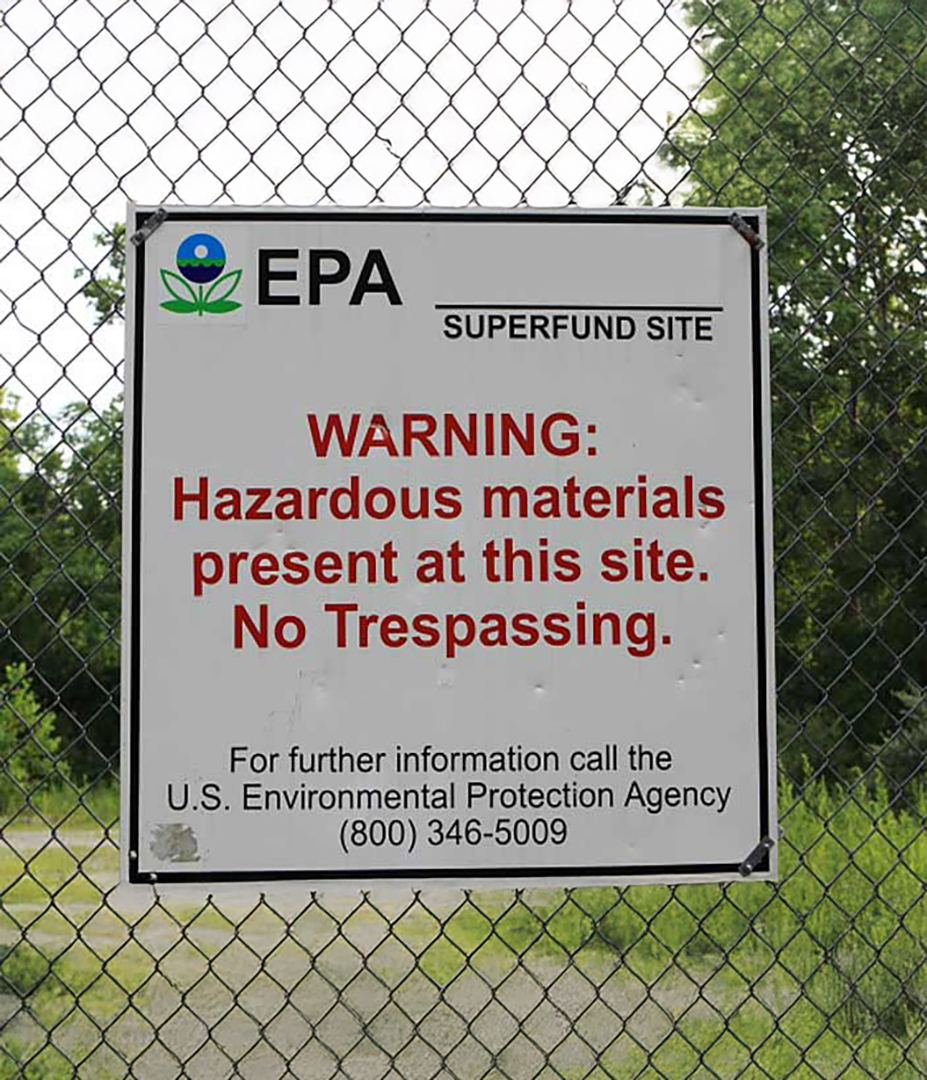

The nation’s hazardous waste infrastructure is required to manage approximately 36 million tons generated each year. While concerns remain about long-term capacity and resilience, overall hazardous waste infrastructure has significantly improved in recent years due to major investments under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). Those investments included $3.5 billion for the Superfund program and $1.5 billion for the Brownfields program, resulting in accelerated cleanup of contaminated properties, enhanced protection of public health and the environment, and economic benefits.

However, as individual per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have recently been designated as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), or Superfund program, addressing PFAS contamination will put significant pressure on hazardous waste infrastructure, increasing future requirements for site investigations and remediation, treatment capacity, and the development of new treatment technologies.

692 current and former Superfund sites are in reuse, supporting over 10,000 businesses and generating more than

$18.8 billion in employment income

$3.5 billion for the Superfund program and has been used to clear the backlog of 49 sites where

clean had been on hold

for the treatment and disposal of hazardous waste through 2044, however if commercial incinerator capacity continues to decrease or a shortage of qualified waste transport drivers worsens

that could change

The amount of hazardous materials both generated and managed has remained relatively stable over the past decade. EPA finds that 34.8 million tons of hazardous materials were generated in 2011, increasing to 35.9 million tons in 2021. In 2011, 1,395 regulated hazardous waste management facilities handled 38.5 million tons of hazardous waste, compared to just 882 facilities managing 37.6 million tons of hazardous waste in 2021. Of those 37.6 million tons of managed hazardous waste, 1.6 million tons were recovered or recycled.

Before the passage of the IIJA, the Superfund budget had been flat for a decade at around $1.1 billion annually. Insufficient funding for the program led to a growing backlog of sites not being cleaned up. The $3.5 billion invested in Superfund through the IIJA was used to clear the backlog of 49 sites where cleanup had been on hold while also accelerating work on new Superfund sites.

EPA indicates that there is adequate capacity nationwide for the treatment and disposal of hazardous waste through the year 2044; however, the estimate does not take into account several factors…

The resilience of the nation’s hazardous waste infrastructure is a growing concern. The core purpose of the nation’s hazardous waste infrastructure is public safety—preventing the release of and exposure to dangerous and toxic substances. While the existing infrastructure is generally fit for that purpose, the resilience of the infrastructure is less certain. Since certain PFAS compounds have been designated as hazardous substances under CERCLA, addressing this type of public and environmental safety concern will put significant pressure on hazardous waste infrastructure with implications on future requirements for site investigations and remediation, treatment capacity, and the development of new treatment technologies.

Remediation technologies continue to improve, and more effective site characterization and cleanup strategies are used to emphasize adaptive management and optimization of treatment systems. For example, EPA’s 2023 Superfund Remedy Report indicates a shift toward greater reliance on in situ and natural systems-based remediation approaches. In situ source treatment increased from 20% to 34%, and monitored natural attenuation (MNA) for groundwater increased from 20% to 31% compared to the previous three years (2015–2017). Meanwhile, EPA’s PFAS Strategic Road Map identifies research as a central focus of EPA’s strategy, enabling greater collaboration between industry, government, and academia in developing new treatment technologies to address PFAS contamination, resulting in more rapid implementation of promising treatment innovations.

Photo Attributions

Select your home state, and we'll let you know about upcoming legislation.

"*" indicates required fields